The following combines elements of Ian Milligan’s tutorial at The Programming Historian, as well as Kellen Kurschinski’s.

Introduction

Wget is a program for downloading materials from the web. It is extremely powerful: if we do it wrong we can look like an attacker, or worse, download the entire internet! We use this program on the command line. We will cover some of the basics, and then we will create a little program that uses wget to download materials from Library and Archives Canada.

Installation

Mac Users

You will need a tool called ‘homebrew’ to obtain wget. Homebrew is a ‘package manager’, or a utility that retrieves software from a single, ‘official’ (as it were) source. To install home brew, copy the command below and enter it at your terminal:

$ /usr/bin/ruby -e "$(curl -fsSL https://raw.githubusercontent.com/Homebrew/install/master/install)"

Then, make sure everything is set up correctly with brew, enter: $ brew doctor

Assuming all has gone well, get wget: $ brew install wget

Then test that it installed: $ wget If it has installed, you’ll get the message -> missing URL.. If it hasn’t you’ll see -> command not found.

Then, navigate to whereever your work for part two of this course is found. Inside your part-two folder, make a new folder and navigate into it:

$ mkdir wget-activehistory

$ cd wget-activehistory

Windows

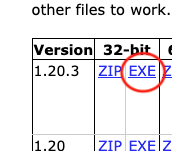

Go to this website and right-click, ‘save target as’ the file for the 32-bit version 1.20.3 EXE file.

Using your file explorer, create a new folder inside your part-two folder and call it wget-activehistory).

Move the wget.exe file out of your Downloads folder into that folder you just created.

Then, open your command prompt and navigate to your newly created wget-activehistory folder. Check that the file wget.exe is in your folder by typing dir.

Basic Usage

Wget expects you to enter the URL to a webpage or some other online file. How do websites organize things? Milligan writes:

Let’s take an example dataset. Say you wanted to download all of the papers hosted on the website ActiveHistory.ca. They are all located at: http://activehistory.ca/papers/; in the sense that they are all contained within the /papers/ directory: for example, the 9th paper published on the website is http://activehistory.ca/papers/historypaper-9/. Think of this structure in the same way as directories on your own computer: if you have a folder labeled /History/, it likely contains several files within it. The same structure holds true for websites, and we are using this logic to tell our computer what files we want to download.

Let’s grab the index page for the Active History website from its papers sub-directory:

Mac:

$ wget http://activehistory.ca/papers/

Windows:

$ wget.exe http://activehistory.ca/papers

Ta da! Look around in that directory, see what got downloaded.

Windows: Going forward, if you see a command for you to type in and it just says wget understand that in your case, you also have to add the .exe. Also, if you try trunning the command from a different folder, you’ll get a ‘file not found error’ because Windows is looking for wget inside the folder where you invoke the command. (There is a way, on a windows machine, to store programs like wget in one directory and to configure things so that the computer always checks that folder first to see if a command/program lives there, but life is too short and the sheer contrariness of windows too great for us to worry about it in this course.)

Specify some parameters

But that was only one file. We’re going to add some more flags to the command to tell wget to recursively follow links (using the -r flag) in that folder but to only follow the links that lead to destinations within the folder (using the -np meaning ‘no parent’). Otherwise we could end up grabbing materials five steps away from this site! (If we did want materials outside of where we started, we’d use the -l flag, ‘links’). Finally, we don’t want to be attacking the site demanding gimme gimme gimme materials. We use the -w flag to wait between requests, and to --limit-rate=20k to narrow the bandwidth our request requires.

-rrecursive-npno-parent-llinks beyond domain we started in-wwait time between requests to the server--limit-rate=limit the bandwidth for our request (which necessarily slows down how long it’ll take to perform the request)

Altogether, our command now looks like this:

$ wget -r -np -w 2 --limit-rate=20k http://activehistory.ca/papers/

Give that a try! This will be very slow. You could try upping the rate, but google around to see what a conventional rate might be. Too much, and you are causing trouble for the website you’re trying to get things from.

Using wget with a list of urls

Let us assume that you were very interested in the history of health care in this country. Through the Library and Archives Canada search interface, you’ve found the Laura A. Gamble fonds, a nurse originally from Wakefield Quebec (just north of Ottawa).

You click through, and find the first image of her diary.

Library and Archives does not provide an ‘application programming interface’, or a polite way/set of commands that we could use on our end to deduce the locations of the information we want. Instead, in a case like this, we have to inspect the underlying html and work out what the actual file name is for the images we want, and where those images live. I’ve already done this for you, but if you right-click on an image, and select ‘inspect’, you’ll get a view of the underlying code powering the webiste, which looks a bit like this:

Suffice to say, eventually you might discover that the pages are for the most part listed numerically, and you can construct a file path to just load those images like this: http://data2.archives.ca/e/e001/e000000422.jpg.

Now, if Library and Archives Canada had an API for their collection, we could just figure out the urls for each image of the diary in that fonds and away we go. But they don’t. Turns out, the urls we want run more or less from …422 to …425 (but try entering other numbers at the end of that URL: you will retrieve who-knows-what!):

- In sublime text, create a new file and paste these urls into it; save the file as

urls.txt

http://data2.archives.ca/e/e001/e000000422.jpg

http://data2.archives.ca/e/e001/e000000423.jpg

http://data2.archives.ca/e/e001/e000000424.jpg

http://data2.archives.ca/e/e001/e000000425.jpg

Now, we know that we can pass an individual url to wget and wget will retrieve it; we can also pass urls.txt to wget, and wget will grab every file in turn!

- Try this at the terminal/command prompt:

$ wget -i urls.txt -r --no-parent -nd -w 2 --limit-rate=100k

(google for wget options)

Using python to generate a list of urls

Now, let’s try something a bit more complex. It’s one thing to manually copy and paste urls into a file, but what if we want a lot of files? You could just set wget to crawl directories, but that can make you look like an attacker, it can clutter your own machine with files you don’t want, and it can mess with your bandwidth and data caps. Sometimes though we can suss out the naming pattern for files, and that’s a situation tailor-made for programming. We will write a small program that will automatically build a file with all of the urls for us, that we can then feed to wget.

Consider the 14th Canadian General Hospital war diaries. The URLs of this diary go from http://data2.archives.ca/e/e061/e001518029.jpg to http://data2.archives.ca/e/e061/e001518109.jpg. That’s 80 pages; you could type in 80 separate wget commands… or you could do this:

- make a new directory for our work - at the command prompt or terminal,

$ mkdir war-diaries, and thencdinto it. - Create a new file in Sublime Text. I’ll give you the script to paste in there, and then I’ll explain what it’s doing.

|

|

First, we’re creating an empty ‘bin’ or variable called ‘urls’. Then, we create a variable called f for file, and tell it to open a new text file for writing, called ‘urls’.

Then we set up a loop with the for command that will iterate over the 80 values from 8029 to 8110. The next line contains our pattern, the full url right up until e0151. The last little bit, the %d takes the number of the current iteration (x) and pastes that in. The \n means ‘new line’ so that when we iterate through this again, we’ve moved the cursor down one line. Then with f.write(urls) we put the pattern into the file. Once we’ve finished - we’ve gotten all the way to 8110 - the loop is done, we close the file, and the script stops.

-

Save this file as

urls.pyin your directorywar-diaries. The.pyreminds us that to run this file we’ll need to invoke it with python. -

At the command prompt / terminal make sure you are in your

war-diariesdirectory withpwdto see where you are, andcdas appropriate to get to where you need to be. -

Make sure the file is there: type

lsordiras appropriate and make sure you see the file. Let’s run this file:$ python urls.py. After a brief pause, you should just be presented with a new prompt, as if nothing has happened: but check your directory (lsordir) and you’ll see a new file,urls.txt. You can open this with Sublime Text to see what’s inside. -

Now that you’ve got the urls, use

wgetas you did for Laura Gamble’s diary (it’s the exact same command). It might go rather slowly, but keep an eye on your file explorer or finder. What have you got in your directory now?

Be a good digital citizen

Always use the wait and limit-rate flags so that you do not overwhelm the server (the computer at the address of your url) with your requests. You can get yourself into trouble if you don’t. Make sure you understand the ideas around recursively following links, link depth, and ‘no-parents.’ Read the original tutorials by Ian Milligan at The Programming Historian, and Kellen Kurschinski for more details.