Podcasting

As you may be thinking to yourself, ‘how can he teach us anything about podcasting, he’s not terribly good at it’.

Fair enough. I first encountered podcasting back in about 2005 - ipod, hence podcasting - as part of my previous life in the edtech world. It was difficult to do, and most ‘shows’ weren’t terribly good. I never really got into it, as a producer. But in recent years, professional broadcasters have entered the scene, raising production values across the board. The tools for making podcasts have made it possible for the likes of you and me to up our game quite a lot too.

For this course, I’ve been using an ipad app from anchor.fm which allows me to record and rearrange snippets, add incidental sound that is license free, and push the podcast to the major discovery platforms. Other folks I know use Spreaker and no doubt there are other platforms out there for building and promoting polished work.

But even if you used those platforms for their distribution reach, or for their access to free-to-use music and sound effects, you might want to consider recording your work with the free and open source sound tool Audacity. Dany Guay-Bélanger, a former public history student here at Carleton, used Audacity and Wordpress to create a podcast series on the problems of archiving video games in a museum context called DeadPlay.

I may not have made many podcasts, but ultimately, they all come down to good storytelling. Terry O’Reilly’s Under the Influence is an excellent example of good storytelling married to a strong structure. Listen to an Under the Influence episode. Every one has the same basic structure. There’s an opening hook that is itself a little gem of story telling with its own internal structure (setup, rising conflict, climax, resolution) that sets the overall theme for the episode. There’s an opening sound/music clip reminding us that we’re listening to ‘Under the Influence.’ The theme is explained in a bit more detail. Then there are three or four more stories more directly germane to that overall theme, and then a final summary that reminds us how the different stories illustrate the theme, with a clever twist tying it all back to the opening hook.

- Why not collaborate with someone on this? Download and install Audacity.

- Follow this lesson by Brandon Walsh at The Programming Historian to become familiar with how Audacity works.

- Record five minutes around the theme of ‘things that have driven me nuts about learning digital history’.

- Have one person collate those snippets into a single file with interstitial music.

- Have one person write and record an opening hook - it doesn’t have to be very long or complex.

- Pull it all together into a single sound file.

Now, is this all feasible given everything else going on right now? Probably not. So: let me be the person who pulls it all together and writes the hook. You just record and tidy up your own snippet, and put that in your repository. I’ll try to get something put together before the course ends to share with all of you in our Discord space.

Sonification

You’re familiar with graphs and charts. In a graph you take the values for one variable and mark them along the x axis. You take the values for a second variable and mark them along the y axis. Where those values intersect, you make a mark: and a simple xy plot is born. Sonification on the other hand maps those values to sonic tones, rather than visual markers. Thus there is also an implicit time variable as you listen; we understand the first tones as being temporally earlier than what we hear at the end. Sonification might be an appropriate technique for understanding historical data.

I have written a longer tutorial on Sonification at the Programming Historian that you might want to engage with more fully; I’ll just quote the opening two paragraphs here:

Sonification is the practice of mapping aspects of the data to produce sound signals. In general, a technique can be called ‘sonification’ if it meets certain conditions. These include reproducibility (the same data can be transformed the same ways by other researchers and produce the same results) and what might be called intelligibility - that the ‘objective’ elements of the original data are reflected systematically in the resulting sound (see Hermann 2008 for a taxonomy of sonification). Last and Usyskin (2015) designed a series of experiments to determine what kinds of data-analytic tasks could be performed when the data were sonified. Their experimental results (Last and Usyskin 2015) have shown that even untrained listeners (listeners with no formal training in music) can make useful distinctions in the data. They found listeners could discriminate in the sonified data common data exploration tasks such as classification and clustering. (Their sonified outputs mapped the underlying data to the Western musical scale.)

Last and Usyskin focused on time-series data. They argue that time-series data are particularly well suited to sonification because there are natural parallels with musical sound. Music is sequential, it has duration, and it evolves over time; so too with time-series data (Last and Usyskin 2015: 424). It becomes a problem of matching the data to the appropriate sonic outputs. In many applications of sonification, a technique called ‘parameter mapping’ is used to marry aspects of the data along various auditory dimensions such as pitch, variation, brilliance, and onset…

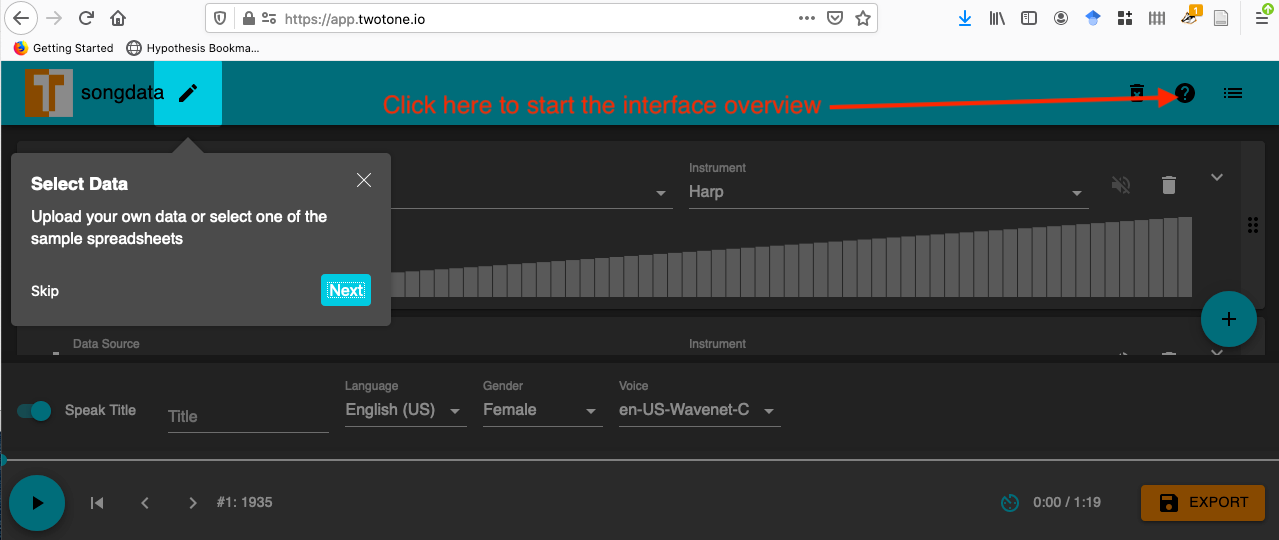

For this exercise I want you to map the data from a historical source (your choice, but if you’re stuck, try some archaeological data) into the ‘Two Tone’ app; click the ? to see how to use its interface. What tones, sounds, settings make sense given your data? How do different choices affect the meaning of what you’ve created? Is there anything meaningful? Save your music and your notes/thoughts on making it, to your repository.