This course originally was a face-to-face class, over 13 weeks. That let us get into the nitty-gritty of different approaches and platforms; it gave us the opportunity to have guest speakers; and most importantly, it gave us the time to really grapple with different kinds of historical ‘capta’ (see Drucker on ‘capta versus data’). But, needs evolved and eventually the course moved fully online. Now only 6 weeks long, a lot of things have been cut, compressed, or rethought entirely. I do not aim for coverage. Rather, I am trying to help you learn the skills that you will need to uncover whatever aspect of digital history method and thought that will help you with your research goals. A big part of that is trying to teach how to deal with what might feel like ‘failure’, on first blush.

Social Contact

Another problem with moving fully online was the isolation. Working with digital tools, especially when you’re not overly familiar with how they work - or even the underlying metaphors that would help you make sense of what’s going on - is frustrating. Bad enough when you have classmates you see twice a week and can at least complain with over coffee later; extremely awful when you’re on a bad internet connection and everyone thinks that you’re not really doing schoolwork.

Initially, I used Slack as a way of trying to meet that need for human connection that makes learning meaningful. It worked, more or less, but if there was a conversation going on and you missed part of it, it could just feel overwhelming and impenetrable.

And it was one more damned thing to install. One more damned thing to get a password for.

I tried Zulipchat another year. Same problem again.

Nowadays, I’m using Discord, for its voice and screensharing integration. We’ll see how that goes.

The Workbook

I put all of the materials for the course into an online workbook, built from text files that used markdown conventions to indicate headings, links, images and so on. The website for the workbook would then be generated using mkdocs, a python library for generating static websites. It worked, but over the years I kept adding more and more to it, links would get broken or websites would go offline… it was a lot of work to prune it, keep it up to date.

And then COVID-19 happened.

I normally have a lot of time to rethink what needs taught, to prune what has become useless, to add newer resources, newer thinking. But this time around, not so much. I put the older version of the course away, and started trying to build what I thought were the most useful elements: given everything else that is going on, what are the key things I think you ought to do in order to plant the seeds of your eventual engagement with digital history?

The result is this present website, which combines a number of features of the course that were previously spread across a number of locations. I have also pared down to a more limited number of skill-based exercises so that you have more time to think about the context (historiographical, theoretical) of their potential use. I offer more direction and less freedom-to-choose in terms of the work I think that needs to be done, but the trade off here is that you are more able to share what you are doing with your peers and to find help.

Which reminds me:

This website is built using Hugo, a static site builder. Static sites are quicker, more secure, and separate content from container, thus making them more sustainable. I write all of the content in individual text files, which I can then turn into whatever output - html, pdf, word doc - that I need. My writing is freed from subscription-based software that might lock it in. I push all of the text files onto github (you can see them here.) Then, I have netlify.com watch those files for any changes. When it spots changes, it uses Hugo to turn them into html, and serves them up at craftingdh.netlify.com.

Some of the work we do requires working with the command line or the terminal of your computer; I also provide a virtual computer that you can access through your browser so that you don’t have to worry about configuring your particular machine to do any one task. This also allows me to write instructions once, and know that everyone will be able to do it (there are always differences between Mac and PC that trip us up). The virtual computer is provided by a service called Binder; I set up a folder on Github with the required bits-and-pieces (think of them as lego blocks) that are necessary for a particular task. I then point Binder at that folder, and it spins up a virtual computer with those pieces properly installed. It then gives me a URL that I can share with you - link on it, and boom! a computer in the cloud ready to go.

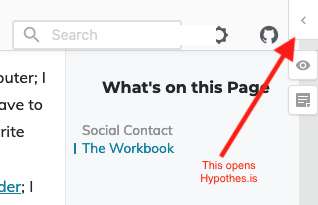

All of this is now under the ‘weekly work’ part of this site. Take your time, annotate the parts that are confusing or troublesome with hypothes.is and you’ll do well.

One last thing

I asked Twitter for its thoughts, as you do:

5 top [method/skills] things students new to digital history should learn. Go!

— Shawn Graham (@electricarchaeo) March 28, 2020

…follow the thread!